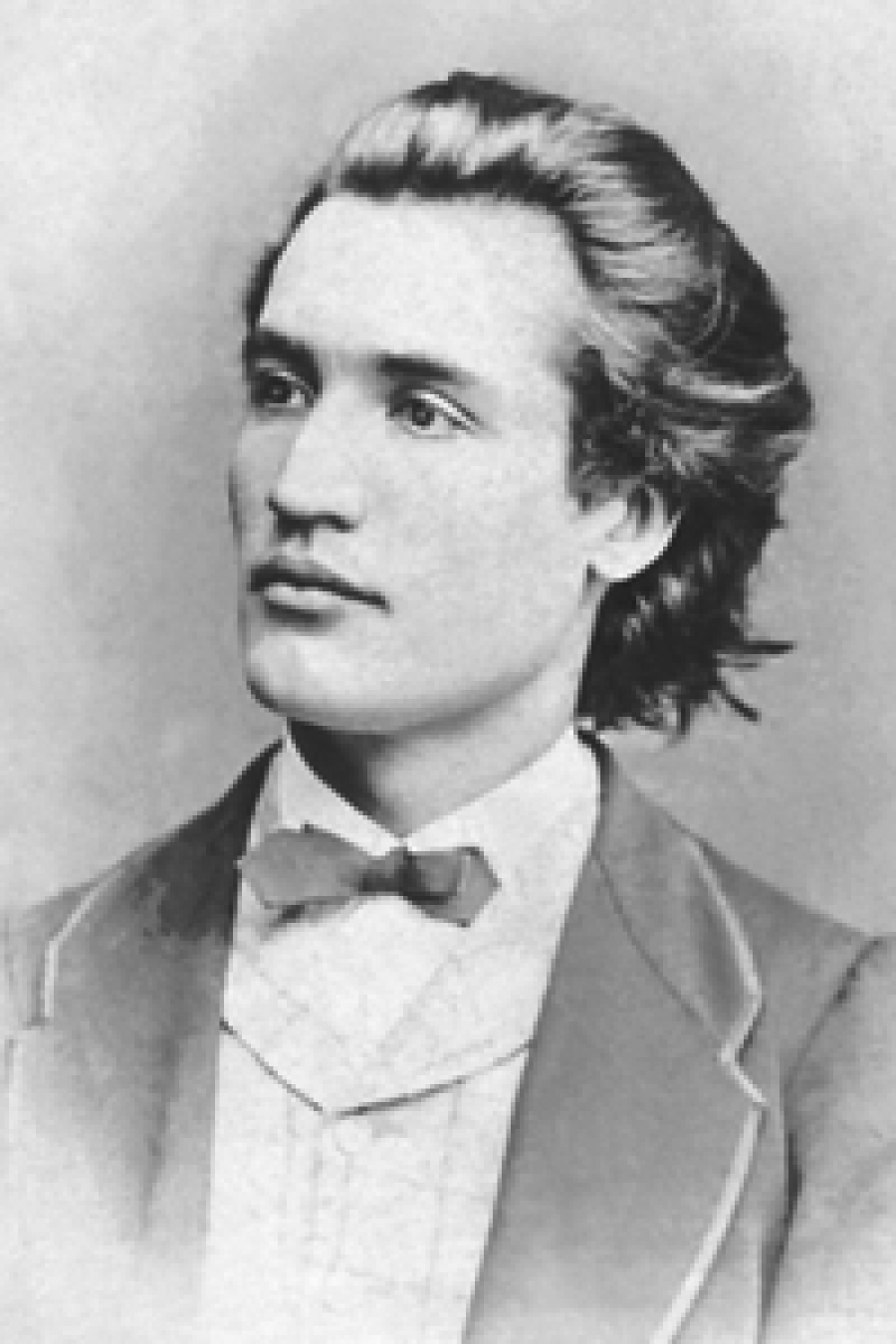

Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Copenhagen.

Education: Duke University, Summer Programme in Transnational Law (1990); LL.M. in Commercial Law, University of Bristol (1992); European University Institute, Academy of European Law (1993); cand.jur. (MA in law), Copenhagen University (1994); HD in international business, Copenhagen Business School (1996).

Employment: Ph.D.-fellow, Copenhagen University (1994-1997); Head of section, Danish Ministry of Justice, Law Department, EU-law office (1997-1998); Référendaire (legal secretary) to the President of the Court of First Instance of the European Community, Luxembourg (1998-2000); Head of section, Danish Ministry of Justice, Law Department, Office on Constitutional Law (2000-2001); Lawyer (parttime), Dragsted Schlüter Aros (2000-2001); Associate professor in EU-law, Copenhagen University (2001-2008); Senior Project Researcher, Danish Institute for International Studies (2007-2008); Associate professor in international development law, Copenhagen University (2008-2010); Professor in international development law, Copenhagen University (2010-2011).

First of all we would like to thank you warmly for accepting this interview.

We have to state in the beginning that, along with Mr Professor Niels Fenger, you authored an important book on the preliminary references to the European Court of Justice.

1. As a first question, we would like to ask you to providea short description of your formative years in law, which is certainly very useful to “apprentices” in law.

Also, is it possible to provide us with a description of your main teaching and research interests in EU law?

Please see CV on my web-page (University of Copenhagen) .

2. From the point of view of the legal order – you arecoming from Denmark – are there any lessons that might useful for a comparative perspective on EU law?

I tend to believe that the Danish legal order does not make a comparative perspective on EU law more useful than do other legal orders.

3. Could you please describe your experiences actingas a référendaire at the European Court of Justice? What are your models among Judges and AGs at the ECJ?

Experience: Assisting President Vesterdorf both with regard to his work as judge and his work as President.

If I should mention one judge who, to my mind, stands out, it would be the late Ole Due.

4. From your perspective, what would be the mainchallenges for the current European Court of Justice?

I believe that the Court is presently challenged by the large number of cases and large number of judges which make it more difficult to attain coherence in the Court’s practice. At the same time much of the Court’s practice today relate to “ordinary cases” which means that it is becoming less of a ‘constitutional court’.

5. Could you please comment on the goals of the competition among European Courts – the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights? What would be the usefulness of an adhesion to the European Convention on Human Rights as far as the European Union has already adopted the Charter of Fundamental Rights?

I do not find myself in a position to give adequate feedback on this question.

6. In that connection, what would be the essence of thereflection document of 2010 concerning the accession of the European Union to the ECHR?

Same answer as immediately above.

7. What is your opinion concerning the “construction”of the principles of the ECJ? What is the role played by preliminary reference?

Principles play an important role in EU law – perhaps the best examples are the principles of derived powers, of proportionality, and of supremacy of EU law. The Court of Justice’s construction of these principles has been instrumental in the creation of the EU legal order.

The preliminary references has played a key role in attaining homogeneity throughout the European Union – and has equally enabled the Court of Justice to develop central legal principles – sometimes on the basis of very minor cases (eg. Costa v ENEL).

8. On the other hand, what role does play the purposiveinterpretation (generally) in law and more particular at the ECJ? Are the any „malaises” concerning this interpretation in the judgments delivered by the ECJ?

At the ECJ, the purposive interpretation seems to hold a privileged place compared to other means of interpretation (systematic, literal, historical). Is this perception grounded? And also, which might be the justification that this kind of interpretation leads finally to a new law?

In my view, it is not correct to claim that today the teleological interpretation necessarily is “the main form of interpretation” of the Court of Justice. A large part of the Court’s caselaw today concerns rather technical matters (interpreting ‘technical’ regulations and directives) and here teleological interpretation is rarely the main approach. In other areas it may be difficult to take a ‘traditional literal approach’ and here a teleological approach is an obvious alternative.

9. Which might be the objective pursued by the ECJ ina case when it answers a preliminary reference relying heavily on facts? Is the division of functions between courts (the national court and the ECJ) still possible in the (current) system of Article 267 TFEU? And also is there still a (genuine) division between law and facts?

On the other hand, are there any dangers in relying on national law in judgment of the Court (not concerning the relevant law, but in the rational building-up of a judgment)?

In general I find that the Court of Justice is duly observing the limits to its competence. At times it is possible to question the Court’s approach.

10. To sum up the above questions: Would there be anyrisks concerning the activism of the European Court of Justice? Is the preliminary reference a strictly legal element or is it a mechanism significantly influenced by other factors – political, economic and so forth?

In your important book on the preliminary reference system you discard the existence of any political explanations underlying the reasoning of the European Court of Justice. But still are there any political reasons behind the reasoning of the ECJ?

It is not possible to give a short answer to the above question. However see chapter II in Niels Fenger’s and my book on Preliminary References.

11. Are there any threats to the unity and coherence ofthe legal system of the European Union? If so, what means should be used in order to overcome them?

At present the main threat to the Union – including its legal order – arguably is the extensive economic crisis that a number of Member States are suffering under. This may well spill over into the legal sphere. In such case it would seem that the solution is political in nature (aimed at the economic crisis).

12. Coming back to scholarly activities: Could youplease provide us with a brief insight of your working methods in writing a book like that concerning the preliminary references? In other words, what means do you employ in gathering and interpreting (and also establishing the relevance of) an enormous record of judgments delivered by the European Court of Justice?

I believe that I use the same approach as virtually all other lawyers – i.e. classical legal interpretation coupled with hard work.

13. And a final question: What advice/recommendation would you give to young researchers in (EU) law?

Probably my best piece of advice is that what you write today may ‘haunt’ you in many years to come if the quality is insufficient. So always be certain that whatever you publish is of high quality.

Thank you very much.

Interviul face parte din lucrarea ”Interviewing European Union. Wilhelm Meister in EU law”, Coordonatori: Daniel Mihail Sandru și Constantin Mihai Banu, Editura Universitara, 2013

http://www.editurauniversitara.ro/carte/sandru/interviewing_european_union_wilhelm_meister_in_eu_law/10468